This Seams Interesting: The Walker Brothers

Hello, I’m Spencer Seams and you’re reading This Seams Interesting. It’s a monthly column looking at weird, interesting, and overlooked people and events throughout history. July’s topic is…

THE WALKER BROTHERS: 60 Years Before Jackie Robinson There Were The Walkers

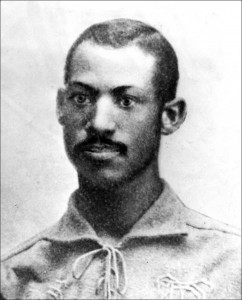

Moses Fleetwood Walker (nicknamed Fleet) and Welday Wilburforce Walker are two of the first black professional baseball players in American history. Some of you reading this might be thinking, “The Walkers weren’t the first, you’re wrong. It was Jackie.” Those of you thinking that, aren’t completely wrong. The first black baseball player to play in the major leagues is not as clear as you’d think. The Walkers may or may not have been the first (depending on your criteria) but they are usually considered to be the first. There were other black players in the majors at the time including George Stovey, William Edward White, Bud Fowler, and Sol White.

William Edward White predates the Walkers by a few years though. William Edward White is recorded to have played only one game. It was on June 21, 1879. It was an athletic battle between the Providence Grays and the Cleveland Blues. White was a first baseman for Providence. Earlier that year, he was part of the Brown University championship baseball team.

White was born a slave in Georgia. His father was white and mother was mixed, black and white. She was a house slave and his father was her master. Will probably passed as white while in the North. On various censuses he was listed as black or white pending on the year and location. He was the first black player to a play in a major league game. Will does not appear to have played any more games besides this one. After this not much is known about him. Technically, he was first but only played one game Again, it depends on your criteria.

With that out of the way, the Walkers. Moses Fleetwood Walker was born October 7, 1856 in Mount Pleasant, Ohio. He was the 3rd out of 6 or 7 children. Welday (Nicknamed Weldy) Wilburforce Walker was born July 27, 1860 in Steunbenville, Ohio. He was the 5th or 6th of 6 or 7 children. Not much is known about the family until 1870. Their father, Moses W. Walker was a doctor turned minister. He and Caroline O’Hara Walker had settled in Ohio as fugitive slaves along the Underground Railroad while on the way to Canada. They were both mixed race.

By the 1870s Baseball was sweeping the nation. Ohio was chock-full of Diamonds, bats and leather mitts. During this time the Walker children attended integrated schools. In 1877, their father became the pastor at Second Methodist Episcopal Church. Fleet and Weldy both graduated high school during these years.

At this point for the sake of clarity I’ll discuss the lives of Fleet and Weldy separately.

Weldy

He started attending Oberlin College in 1881, following his older brother Fleet. The sports department had no rules against blacks playing with whites. It was student ran as opposed to having the NCAA in place. Oberlin had integrated by this point. He played on the Oberlin Yeomans baseball team with Fleet for a season. After a momentous game against the University of Michigan in 1881. Fleet was recruited by U of Michigan and transferred there. Again, Weldy followed suit a few years later, by transferring to the Homeopathic Medical School at University of Michigan.

Just like Oberlin, seemingly no one cared they were black. Apparently the student body was surprised to learn their star players were black but that was the worst thing to him while there. Weldy played together for a season there. Fleet left for the minor leagues but Weldy decided to stay. He continued his college career until spring 1884. He left school to play in the Majors with Fleet.

Weldy was a professional leftfielder for the Toledo Blue Stockings that summer. He made his major league debut July 15 versus the Philadelphia Athletics. He only played 3 or 4 more games that summer. His last major league game was August 6, 1884 against the Indianapolis Hoosiers. Both he and Fleet were kicked off the team at the end of the season, they never played in a game together with Toledo. Weldy did not follow brother again.

This marks the turning point for Weldy. He and a friend started a restaurant, the Delmonico Dining Rooms, in Mingo, Ohio. Much like his Major League baseball career it folded shortly after starting. After he sold the Dining Rooms, the Walker brothers managed the LaGrande Opera House in Cleveland, Ohio. This kept him afloat so he went back to baseball, it was the minors this time.

He played 3rd baseman for the Excelsior Club in Cleveland briefly in 1886. This was followed by a brief stent in 1887 with the Ohio State League’s Akron Acorns. Later that year, moved to the Pittsburgh Keystones in the League of Colored Base Ball Players. That league folded after 2 weeks. He tried unsuccessfully again this and managed /played for the Keystone Base Ball Club of East Liverpool (still in Ohio, not that Liverpool) in 1888. By this point it was segregation was becoming more widespread in baseball. Weldy wasn’t having it.

He wrote an impassioned letter on racism within baseball to the Ohio State League but it led to nothing. His activist spirit never died and only grew as he got older. In 1886, he and a black friend walked into a ‘white’ roller rink to integrate it. They were refused service and sued. Weldy won that case.

Aside from baseball and owning several businesses throughout his life, he was very politically active. His primary focus was black issues. The color barrier went up officially in baseball after he and Fleet left sports. He was a strong supporter of the Back-to-Africa movement and worked as an agent for Liberian emigration. He strongly believed in racial separation and was also on the Executive Committee of the Negro Protective Party in Ohio.

He continued being active in the push for integration and black rights. Weldy made a living as a successful business owner by this point. In 1897, established a fish and oyster store. Shortly after this he started managing the Union Hotel until he died. Thomas, his nephew, helped him the entire time. During the Roaring 20’s he was a moderately successful bootlegger but was eventually caught and indicted.

On November 23, 1937 at 78, Weldy passed from influenza. He never married.

Moses aka ‘Fleet’

In 1877, a 20-year old Fleet started Preparatory Program at Oberlin College. A year later, he officially enrolled in the ‘classical and scientific course in the Department of Philosophy and Arts.’ His grades started great but once he joined the baseball team, they fell off. Initially, the only play was inter-play but they expanded to other schools shortly after. Fleet were the stars. His final game with Oberlin was against Michigan in 1881. The Oberlin Yeomans lost 9-2. U of Michigan offered him a spot on the team. Moses became the first Black athlete in University of Michigan’s history.

During the summer of 1881, he played semi-professional baseball for the White Sewing Machine Company of Cleveland. This led to the first of many instances that would follow Fleet during his athletic career. The day was August 21. The game was on the road in Louisville, KY. When Fleet took the diamond, things turned ugly. The audience wasn’t happy and the home team was furious. 2 of the Kentucky players, Fritz Pfeffer and Johnnie Reccius, refused to play with a black person on the field. Fleet played until the 2nd inning and returned to the bullpen.

Baseball wasn’t the only reason, Fleet left Oberlin. While he was there, he met two women, Arabella Taylor and Ednah Mason. He was romantically involved with Arabella. She was pregnant around the time of the Michigan game. The Oberlin community wasn’t a great place for an unmarried pregnant woman. They packed up and moved to Michigan. In 1882, she had a daughter named Cleolinda. They had 2 more children, Thomas, in 1884, and George, in 1886.

Fleet played for the Wolverines for 2 years. In 1883, he left school to play in the minor league. He played catcher for the Toledo Blue Stockings. During his first year with the Blue Stockings he had a run in with Cap Anson. They met on the diamond on July 1883. Anson was a major player on and off the field. Everyone respected him and followed his lead. He was also a racist. He refused to play with Fleet on the field. Because of Anson he sat out for the game. A handful of years later, Anson (A Hall of Fame player) spearheaded the establishment of the color barrier in baseball. At this point, it was the Air Bud rule of, “There’s nothing in the rule book that says we can’t.” It just wasn’t a common practice at the time. There were several incidents like this during the season and his career.

A year later in 1884, they became a major league team. On May 1, 1884 against the Louisville Eclipse he played his first Major League game. Injury cut Fleet’s season shorter than expected. He did play 42 games and was cut from the team September 23, 1884. He became a Postman in the meantime.

Hope was not lost though, Fleet signed with the Western League’s Cleveland Team. He played all 18 games until that league folded. To support himself, he and Weldy ran the LaGrande Opera House together.

Over the next few years, he played on Newark Bears with George Stovey, and the Syracuse Stars. He was the last black player in the Minor Leagues or Major League in 1889. While with Newark, they played an exhibition game against Cap Anson…again. Stovey and Fleet sat the game out. His final day of his baseball career was August 23, 1889.

He held a variety of jobs after this. They include Postman (again), business owner, railroad clerk, author, and inventor. The family remained in Syracuse for a while. The 1890s were a rough time for Fleet. In 1891, Fleet was drinking at a bar when a group of white men were picked him as a target. They insulted him and things turned ugly. A brawl ended up breaking out. Fleet drew his knife and ended up stabbing one of the white men that caused the brawl. He died. In court, Fleet was surprisingly acquitted of murder by all-white jury.

The family stayed in Syracuse. Arabella died from cancer in 1895. A few years later married Ednah Mason, another Oberlin Alum. Both of his parents died by the end of decade. The finale to the 1890s was Fleet getting a felony charge for stealing mail. He spent a year in federal prison for a felony. After his release the family moved back to Steubenville.

He joined his brother in the fight for equality. They ran a newspaper that specialized in black issues, The Equator. He strongly backed the Back-To-Africa movement and racial separation. He helped run the Union Hotel too. Aside from politics, he ran another opera house. This one was in Cadiy, Ohio. In 1908, published a book titled, “Our Home Colony: A Treatise on the Past, Present, and Future of the Negro Race in America.” This was his dissatisfaction with the progress that was supposed to have happened by then. Fleet had 4 patents as well. 3 of them were improvements on film projectors and the other one was an improved explosive artillery shell.

He sold the Cadiy Opera House in 1920. Ednah died that year as well. He died from pneumonia May 11, 1924. His grave was left unmarked until 1991.

The Walker Brothers weren’t perfect. They played professional baseball but it wasn’t the right time. They weren’t just athletes. They were well spoken, educated, passionate, and strong people. The primary reason they’re overlooked is Jackie Robinson. He wasn’t the first but his story fits the mold of sports hero in a better, more complete way. Another reason is the Walkers’ politics. They strongly supported racial separation. The Civil Rights movement at that time is broken into 2 camps, Integration and Separation. The Integration side looks better in retrospect than the Separation side. This side may not resonate with people now as much as it does then. The Walkers’ Baseball is dead and mostly overlooked or ignored. Jackie’s Baseball is still very much alive. It’s a crime the Walker Brothers’ accomplishments and legacy are largely forgotten.

References:

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/w/walkefl01.shtml

http://mlb.mlb.com/mlb/history/mlb_negro_leagues_profile.jsp?player=walker_fleetwood

http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/9fc5f867

http://www.blackpast.org/aah/walker-moses-fleetwood-1857-1924

http://www.miamisci.org/youth/unity/Unity1/Kareem/pages/FleetWood.html

http://coe.k-state.edu/annex/nlbemuseum/history/players/walker.html

http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/08893f9f

http://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/june-21-1879-cameo-william-edward-white

http://blackathlete.net/2008/06/cap-anson-and-the-color-line/

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/w/walkewe01.shtml

http://articles.philly.com/2007-04-12/sports/24993709_1_black-freemen-black-teams-andrew-rube-foster

http://www.baseball-reference.com/minors/player.cgi?id=walker001wel

Craig Brown

We could use your help to honor Moses Fleetwood Walker. Drop us a message.

https://www.facebook.com/mosesfleetwoodwalkerday/

Also, Bud Fowler, George Stovey, and Sol White were not MLB players. White played one game, but no one knows if he played openly as a black man. Where did you get the fugitive slave info about Ma and Pa Walker?

CB